Earlier this year, highly successful fintech company Wirecard appeared poised to buy Deutsche Bank, a sale that could have finally buried accusations of fraud deep in the books. They might have gotten away with it if it weren’t for one determined reporter who relentlessly followed the paper trail and exposed the biggest corporate scandal since Enron.

Earnest coverage of Wirecard’s questionable finances began in 2015, however, spreading the full story across dozens of in-depth articles. For those interested in the Cliff’s Notes version, let’s dive in.

The Tech Darling That Was Too Big to Fail

Founded in 1999, Wirecard narrowly survived the dotcom bubble burst. By 2006 the payment processing upstart was officially listed on the Frankfurt stock exchange. From there, growth was rapid.

However, signs of trouble began surfacing as early as 2008. Investor representatives noticed irregularities in Wirecard’s balance sheets, prompting a special audit by Ernst & Young. Two Wirecard employees took the fall, EY earned itself the cushy role of chief auditor, and Wirecard emerged unscathed.

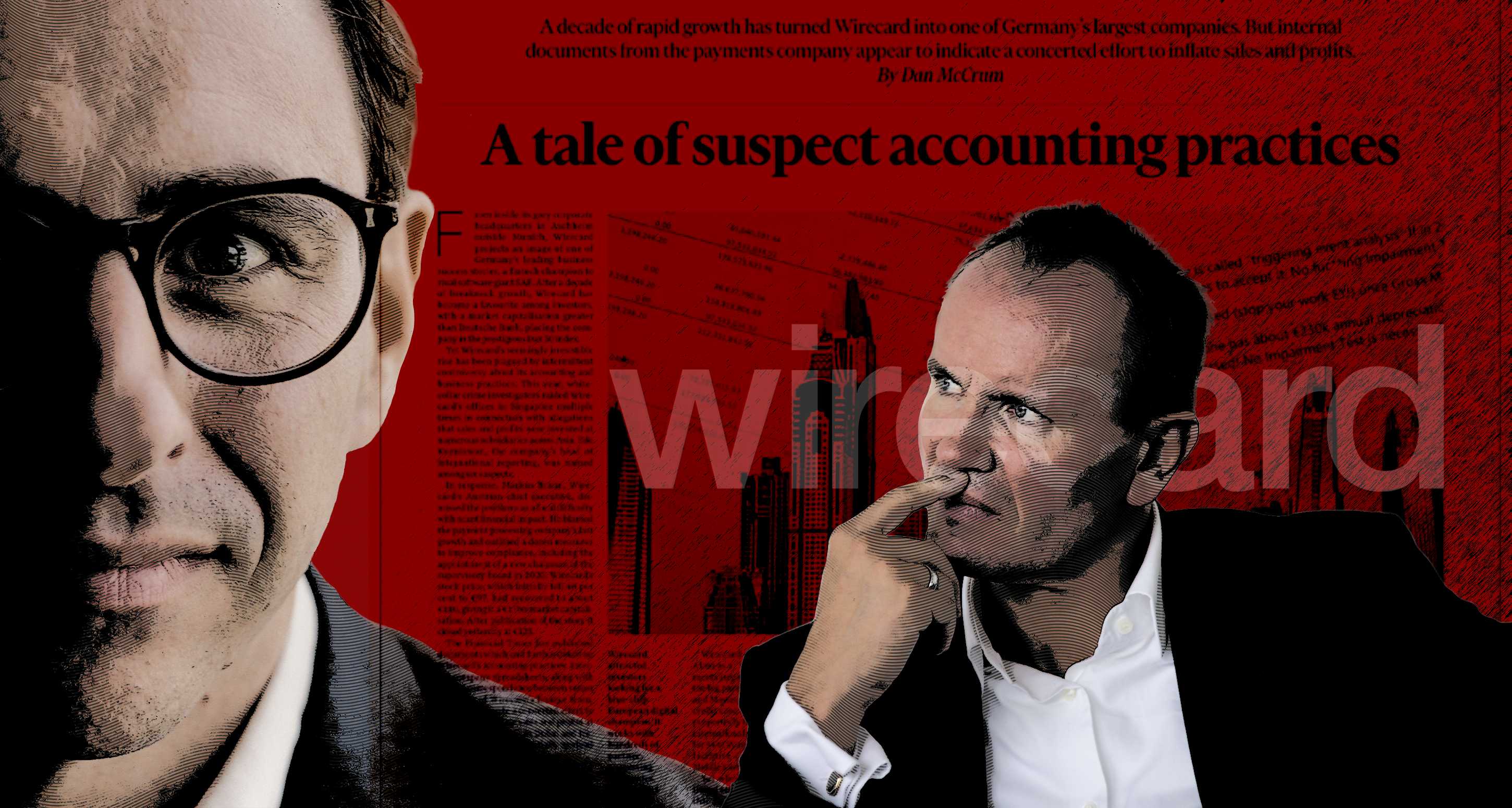

That is, until 2015, when Dan McCrum of the Financial Times reported a €250m gap in Wirecard’s balance sheets. McCrum wasn’t alone in his suspicion of Wirecard. Short sellers at Zatarra Research accused the company of laundering money and overstating its reach in Asia in 2016. Yet, EY reported a clean audit in 2017, and company share values doubled. The following year, Wirecard replaced Commerzbank on the DAX30 index and surpassed Deutsche Bank in value.

At that point, Wirecard was officially Germany’s tech darling—Europe’s answer to Silicon Valley giants. With CEO Markus Braun’s assurance that sales and profits would double by 2020, investors went all-in.

At the FT, McCrum uncovered a different story. There was a stalled investigation for forged contracts in Singapore, and questions about partners in the Philippines. When McCrum’s colleague went to visit a supposed partner office, she found herself at a retired seaman’s home.

Wirecard dismissed the FT’s findings, temporarily placating investors and regulators who were eager to believe that the company’s success was legitimate. However, police raided their Singapore offices in February 2019 and unearthed evidence of a round-tripping scheme: Wirecard was sending fraudulent funds to businesses in India to create the appearance of increased acquisitions and revenue. Investors were stunned. As share prices plummeted, Germany’s financial regulation authority announced a two-month ban on short-selling Wirecard due to its “importance for the economy.”

The Bigger They Are...

The following month, the FT reported that half of Wirecard’s business was outsourced to payment processors who paid Wirecard commissions into unverified escrow accounts. Braun dismissed the claims, and withdrew €900m from Japan’s SoftBank to dispel any notions of foul play in Asia and reinstate public confidence at home.

In September 2019, Wirecard went on the offensive, suing the FT for “misuse of trade secrets,” alleging its reporters were making money by short-selling the company’s stock hours before their negative press went live. German regulators appeared to side with Wirecard, investigating the FT staff involved in reporting on the company.

Meanwhile, McCrum and his team uncovered a long list of fake customers in Wirecard’s financial reports, indicating that significant profits were fraudulent. Wirecard once again denied McCrum’s findings, and appointed KPMG to conduct a special audit. After a delay, KPMG reported in April 2020 that it had encountered obstacles and could not verify “the lion’s share” of Wirecard profits from 2016 to 2018. EY’s annual audit too was held up, awaiting confirmation that two bank accounts in the Philippines held €1.9bn—most of Wirecard’s reported profits—in escrow from partners.

Braun and Wirecard insisted everything was fine, underplayed the KPMG report, and claimed that EY was prepared to report a clean audit. Less than two weeks later, the Phillippine banks that supposedly held €1.9b of Wirecard funds informed EY that the bank documents were “spurious”. There was never any money; there were never even accounts. Police raided Wirecard’s Munich offices in June.

After a rush of statements, suspensions, and resignations, four former Wirecard executives are now in police custody, one is on the run, and another has been reported dead in the Philippines. Wirecard filed for insolvency in late June, leaving Germany’s finance sector, not to mention many of its citizens’ pension funds, to pick up the pieces.

What Can We Learn From Wirecard?

Wirecard’s boom and bust prompt many questions, but perhaps the biggest one is: How did regulatory agencies, auditors, and others let Wirecard get away with this?

The answer may lie somewhere at the intersection between archaic auditing practices and disruptive fintech business models. Auditors and regulators default to the belief that a company’s success is due to some “technical magic” they don’t understand, creating a forgiving environment for shallow audits. Meanwhile, big fintech companies earn favor with officials, legally or otherwise, increasing the chance of an averted gaze.

If it weren’t for reporters like Dan McCrum, how much longer would the shady dealings have gone on? With regulators and auditors wrapped up in Wirecard’s success, who stood in the way? Meanwhile, how many other scandals went unnoticed? And why does it always seem like investigative journalists are doing regulators’ jobs?

Until advances in financial technology are met with an analogous evolution in auditing and regulatory practices, these damaging scandals are going to keep happening. And we’re going to need more than intrepid reporters to keep them in check.