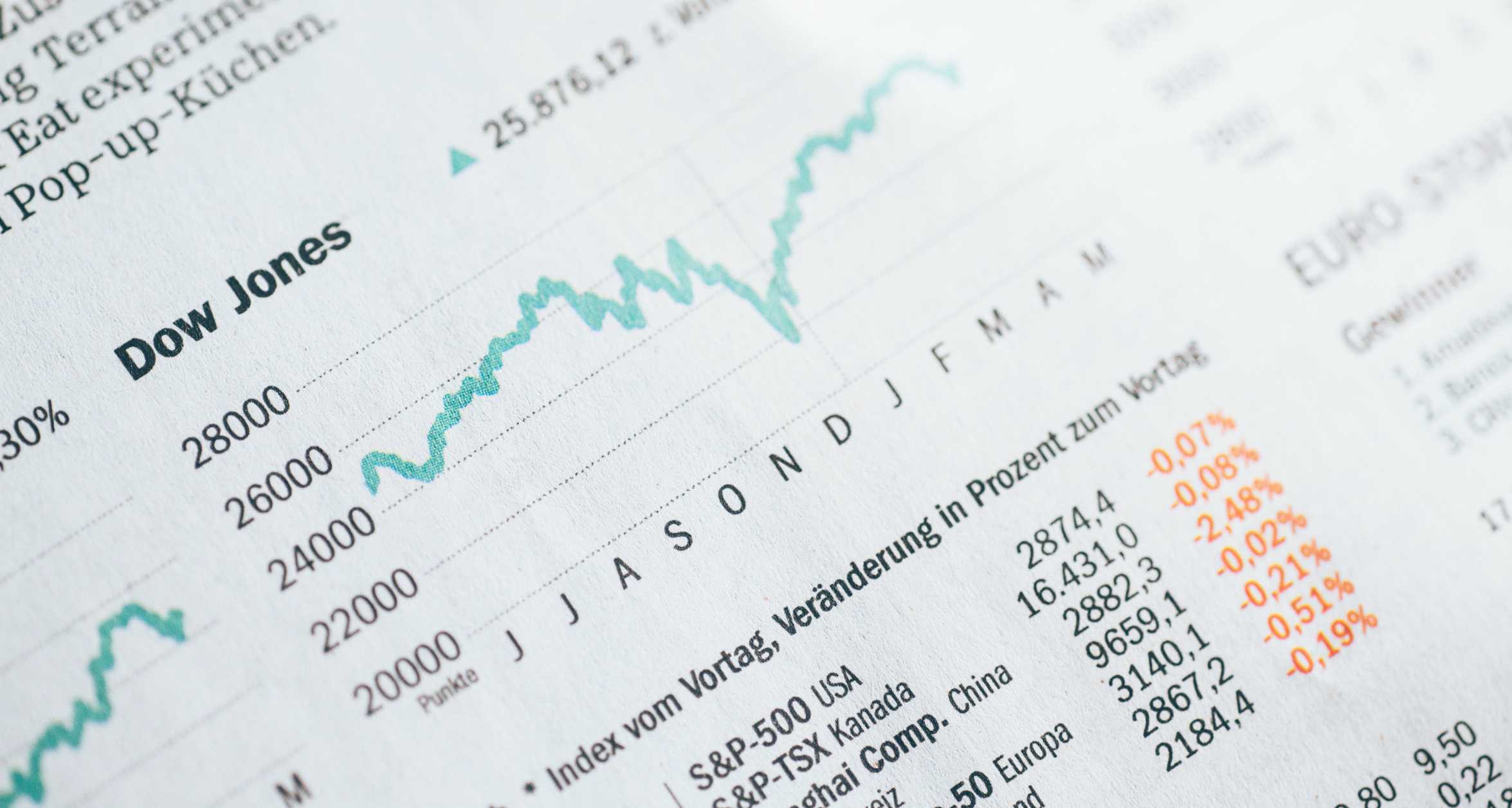

On March 23, the S&P 500 plunged almost 34 percent from its February 19 record high, to a record low.

But it has subsequently rallied against the gravity of the situation: a collapse in consumer spending, an anticipated huge fall in the GDP and a record number of unemployment claims. If you only looked at the stock market, you’d have little indication that a global pandemic and Great Depression-like conditions have hit the streets of the United States.

The question is: why?

Some observers attribute the rebound to the federal stimulus and the likelihood of future installments. Others have pointed to the Federal Reserve Bank’s commitment to inject liquidity into the market, buying as much government and corporate debt as necessary—thus supporting the flow of credit.

In March, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis president Neel Kashkari told CBS’ 60 Minutes “There is an infinite amount of cash in the Federal Reserve [and] we will do whatever we need to do.”

There’s also another driver, according to investment banker Matt Levine in Bloomberg News: a boom in individual trading that is propelled by lockdown boredom.

The fun factor

Bloomberg reporter Sarah Ponczek has separately pointed out that giant retail brokerages—E*Trade, TD Ameritrade and Charles Schwab—each saw record signups in Q1, with a significant increase during March.

TD Ameritrade, for example, reported $45 billion in net new assets for Q1, with 58 percent being retail (individual) investors, and said it added more than four hundred thousand accounts in March. Discount brokerage E-Trade recently announced that its daily trading volume for this past April was three times more than the same month, a year ago.

All three brokerages also recently eliminated commissions for buying and selling stocks, which is obviously another factor in the increased activity. But many of the individual investors “are not trading because they have an informational advantage and a reasonable expectation of profit,” Levine contends.

Instead, he said, “they are trading because it is fun, or because it looks fun.”

The coronavirus crisis has “eliminated most forms of fun,” he said, like dining in restaurants, going out dancing or going to the movies. According to this theory, trading stocks through an app like Robinhood—with quick and easy interaction and zero trading commissions—is not unlike the engaged activity of a good mobile game.

Gambling, fun and entertainment

Or like gambling. Ponczek cites DataTrek Research cofounder Nicholas Colas, who says that Google Trends data shows “some of the action [from closed casinos/sports betting] went to stock markets.”

As with the rollercoaster rides of the bitcoin craze and the popularity of financial TV like CNBC, speculative investment has become a kind of entertainment. Like movies or live sports events, this kind of entertainment has its share of dramatic moments, disappointments, plot turns and triumphs.

Of course, fun or entertainment aren’t the motivating factors for big institutional investors, whose decisions drive much of the market.

But, even if the trades of individual investors make up only a small part of the market’s activities, their collective movement can still have a giant effect. It’s possible, for instance, that the boom in new accounts set up at TD Ameritrade and the like may have factored into the decisions by institutional investors.

Creating the conditions for gamification

Consider the game of poker. It requires skill, assessment of risk and some self-control. It also requires luck, a dynamic factor that reflects how the gods of poker play with poker players.

When you do it well, you can win money. Few things are more pleasurable than walking away from a game with more cash in your pocket than when you entered.

These factors—skill, risk assessment, self-control, luck and smart responses to luck—are all key elements in any interactive entertainment, whether poker or a mobile game. Add in the possibility of making money and the relatively quick action enabled by today’s market feeds, and you have the reason why stock market investing is not like its other financial cousins, such as buying insurance.

In fact, the entertainment value of investing is the explicit driver for the popular financial app Robinhood. On its web site, Robinhood describes its goal as making investing “more affordable, more intuitive, and more fun.”

Not mentioned as a goal: helping you make money.

Not your grandfather’s idea of finance

The Internet has transformed stock market investing by slashing commissions and making tools easier and more accessible. Satya Patel, partner at Homebrew Ventures, explains that these tools have given Americans access to previously inaccessible ways to grow wealth:

"Historically, the best ways to create wealth were through real estate and stocks. One of those is much more accessible now than it was even a decade ago. You can research and buy stocks from your phone and you can do that with zero commissions. That's made individual investing more attractive."

The new applications also heighten investing’s intrinsic entertainment value, with appealing interfaces, a variety of fun-to-use options, and tools that allow a player to manage performance, much as a video game player might manage her energy level and powers.

Watchlists, for instance, let investors track the price changes of multiple stocks, and notifications alert them when the opportunity for a new investment move comes up. And new kinds of graphical tools, like Japanese candlesticks, make it easier to quickly see how stocks have performed.

The Acorns and Stash apps allow investing with very small amounts of money. Stockpile similarly offers trades for 99 cents, and adds the ability to give an e-card or physical gift card that is redeemable as stock.

Even though new-wave financial applications like Simple.com (“a bank that doesn’t suck”) or TD Ameritrade’s thinkorswim advanced trading platform don’t push themselves as much toward financial gaming as, say, Robinhood, they do move in that general direction. A fast, easy-to-use, graphically-based and colorful interface, and a limited use of obscure financial jargon, goes a long way toward building a user base among customers, especially younger ones.

What are the limits of gamification?

There are risks, of course, to treating financial investing like a game.

“The casualization of trading makes money more ethereal, like a token in a video game,” senior lecturer in media and communication at Australia’s Swinburne University of Technology Dr. César Albarrán-Torres told Business Insider last year.

“This makes gaming the system not seem like a big deal,” he added, “but rather a playful and inconsequential action,” such as the use by some players of a now-closed “infinite money” glitch in Robinhood.

Some promoters of the idea that gaming and finance belong together include renown design firm Frog Design. In a recent post on his firm’s blog, for instance, Executive Director David Zemanek provides a rundown of gaming principles for fintech—but the emphasis is on applications for savings practices.

Savings—a habitual activity that benefits from methodical additions into a few well-considered pots—is a very different kind of activity than investing, which is ultimately a form of gambling. Zemanek’s suggestions make sense to encourage savings and related financial education, but they have limited application to investing.

Similarly, a 2017 post on the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s blog examined “The Gamification Effect.” Interestingly, that game-based approach isn’t posited for investing, but for financial education and savings programs.

The drawbacks to investing as entertainment

Both of these posts advocate a gamification approach that can benefit financial savings or financial education, because those are necessary endeavors for financial security that commonly elicit big yawns.

But the entertainment value of financial investing, even with such shiny new apps, has built-in limits if your goal is to actually, you know, make money.

First of all, very active stock trading may not be the most tax-effective or investment-wise way to see your money grow. And, without active trading, there are only so many things you can do in an investing app.

Second, while gamified apps offer such difficult-to-understand stock trading actions as puts, calls and buying on margin, it’s easy to misuse them.

When you are confused about ways to conserve battery power or acquire new powers in a mobile game, you might lose some points, or maybe a few of your many lives. But when you misunderstand margin buying and your retirement nest egg is suddenly cracked and drained,

you can’t just reboot the app and start over a new life.

Better than a trip to the dentist

Even if the entertainment value of financial investing has its limits, the appeal of fun across fintech is something that all financial and marketing executives should note.

Only a few years ago, financial management by individuals maintained its stature as being one of those many boring things you had to do as a grownup.

Even today, the annual presentation by an employer’s 401(k) manager is often greeted with all the excitement that accompanies a trip to the dentist.

But, now, investors don’t have to file papers or struggle to understand arcane jargon from a broker. Instead, they’re riding a bull or dodging a bear, often in tiny slivers of investments that even low-net worth individuals can enjoy.

This changes the potential appeal of financial products or services of all kinds, and can affect their design, purpose, functions and marketing.

CapitalOne, for instance, has said it is “re-inventing” banking, with branches designed to resemble cafes instead of bank offices. Liberty Insurance has offered a “Best Driver” competition, as a way of providing “something fun, interesting and meaningful,” while other kinds of gamification have become a significant trend in that industry.

An enjoyable approach to financial activity is now becoming common, whether it is more customer-friendly banking or an investing app that borrows from gaming. This overall trend counters the somber approach long championed by many of the gray beards in finance and economics.

"Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow,” Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson once said. “If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas."

But he misread the future of finance. Today, you don’t need $800, you don’t need Vegas, and the rewards can be more quickly revealed than in a long-term staring contest with your front lawn.